Have you ever been on walking around going somewhere and you know, out of nowhere it starts raining? Yeah, that sucks, specially if you are not prepared. In fact, I just nearly got caught in one, in the time when I am writing this post. Given that getting wet on the rain is one of the biggest plights on the world, obviously, there are millions of people heavily invested in finding the definitive answer: “Is it better to run or to walk on the rain?”

Or rather, there were. Because there is actually an answer. Several even, but all invariably settling on the solution that running is better than walking, with some additional caveats and dependencies on angle, surface area and wind speed [1-5]. So, it is done, right. The blogpost is over, what are you doing here? I should be writing something else, maybe finishing the posts to the Measurement series, which have been late for a few months now. Or is it? (Hey VSauce!!!)

You see, when I first started this post, I had a vague sense of dissatisfaction with the solution. Not because it was wrong, it is very sound. But because it felt so simple, so “trivial” for lack of a better word, that I basically felt I should try to look closer into the problem. My aim here is not to disprove things, specially because those predictions are already confirmed experimentally [5]. I am more interested in understanding what assumptions were made for the original model, and how changing those assumptions change the results. And specifically, I want to consider the extremes of the model to see if we recover reasonable predictions.

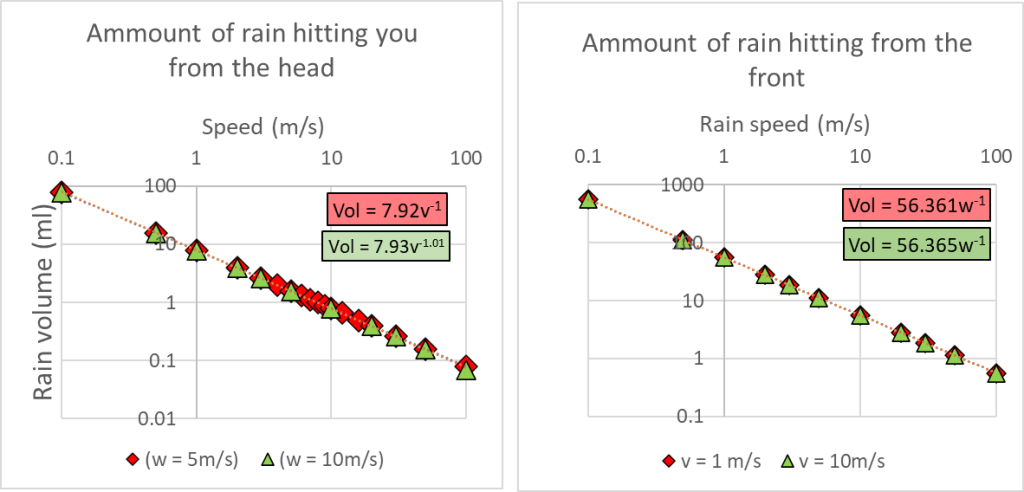

Let’s start with the resource provided in [6], where you can estimate the amount of rain hitting you from the front and from the head. It would be a bit of a pain for you to look for a different range of behaviors one by one, so I decided to look it up and organize it for you instead. I left all of the default parameters unchanged, and only varied the speed at which you will be walking/running, and the rain drop speed. Below you have a graph of the results for a wide range of values.

For simplicity w is the rain speed, and v is your speed. But a couple of things become evident. The amount of rain hitting you from the head doesn’t seem to depend on the rain speed, only depending on your speed, and decreasing over time. On the other hand the ammount of rain hitting you from the front does not depend on your own speed, rather only on the rain speed. Given this fact, you can say that the amount of rain hitting you in total can just be added as independent components of your speed and rain speed.

Since you can’t control how fast rain falls, this may lead you to conclude “Well, I guess I just have to run as fast as I can”. The coefficients there may be confusing but we can tell a bunch from the way they are related. The ratio between the coefficients is equal to the ratio between areas. So, if you factor out the areas and the time takes to cross a distance d (since you assume a constant velocity v, this is d/v), you get

This expression may sound complicated but what it is really telling you is that the total amount of water you carry just depends on two things:

- The time it is takes to cross the distance d (which only depends on v)

- The effective area that is crossed during the travel, which is the same for the head and changes for the front because of Galilean relativity (basically the rain makes an angle when falling over);

- The flux, which is the amount of stuff going through some area over some period of time, so:

Total amount of stuff = Flux x Area x Time

This of course should settle the discussion right? Except, that I think there may be some issue with the expression above. Now for the Head area, things are fine, they seem to be alright, the rain is falling vertically and we assumed an uniform rain fall. For the frontal area, the interpretation seems to be that the faster you go, the more drops of rain hit you, but the only thing that matters is the angle that hits you, so you consider Flux x Area x Tan(Angle), where the tangent of the angle is given by v/w. The main problem I have with this formula is that the for high speeds the effective front area seems to approach infinity. If instead we consider Sin(Angle):

We now have something that works both for limits of low and high speed, and it is actually how you relate flux and area (Well you would actually consider the Cos(Angle) but the angle we consider there is complementary to the one in the actual formula, so the switch works) [7]. There is another way we can improve upon this model. You see, the way things are now, if you were to just stand still on the rain, hypothetical you could hold an infinite amount of rain drops. But we know we can only hold a finite amount. What that amounts is changes with the materials and stuff, but you could say everything can only hold so much water before it becomes wet. And while it’s not clear where we draw the line between something being wet or not, I would say we can draw a line on how wet something is. The Flux x Area term, we can assume to be constants over time, as they do not depend explicitly on it (despite time itself depending on velocity). So we can basically assume that what we have is something of the form

Stuff = Current x Time

Where Current is the amount of stuff over time or in this case, the amount of rains hitting you over time. Through some dark magic we call calculus, we can impose the condition for the total amount of water capping of at some value N0 which we can call the saturation value. It ends up giving the following expression:

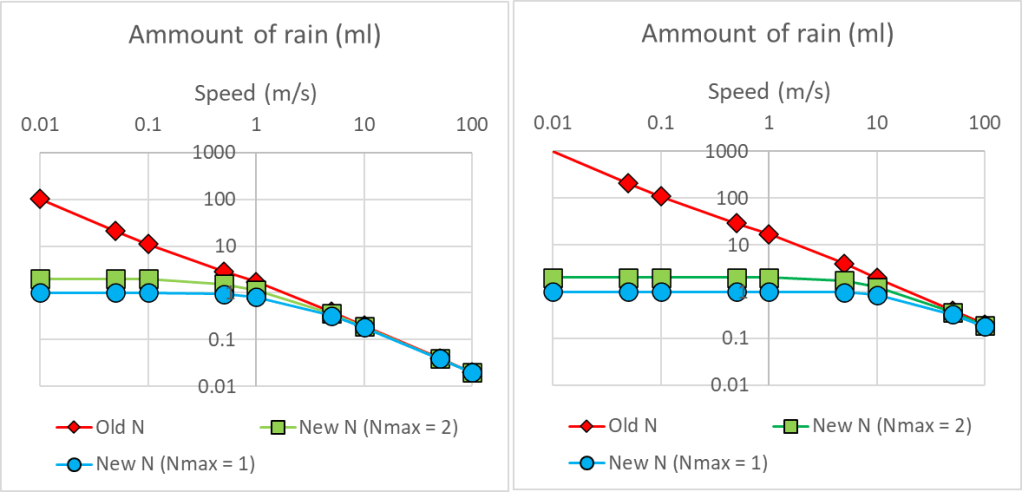

It looks way scarier if I expand the old NTotal expression with what we had above. But really what this tells us is that it still behaves like the other function for high speeds, but near 0 it doesn’t blow up, instead capping of at zero. Does this change any fundamental result we had before? Not much really. It just tells us a bit about the minimum speed you need if you want to not get wet.

In this image we have the amount of rain for a fixed rain speed, but for different fluxes (the flux for the image in the left is 10 times the one on the right). It is possible to see that depending on the flux and on the saturation value, there are some values for which the wetness barely changes, while for large speeds it basically corresponds with the old estimate. For a really high flux, apparently walking and running barely changes anything. Which also fits with the common experience, when it rains, if it pours, running will only waste your energy. But hey you can still do it if that’s your vibe. But sometimes it is not pouring, and in those cases, maybe you should run. In fact, since it has two kinds of behavior, we may even try to predict when one should run or just walk if it is not worth it. To do so we will compare the total amount of rain in your body by relating your velocity to a parameter we will define as $\beta$ (I forgot how to write Greek letters here) that also has units of velocity.

From [6], we know that people can walk from around 1 m/s to 10 m/s if you are an Olympic runner. So what we are going to look at will be the total amount of rain we get, color coding it red if it is above 50% of the total wetness, and blue otherwise, but only for velocities in this range.

And there you have it, while running maybe the best for circumstances in which you just have a drizzle or distance is short, it actually doesn’t matter much if you are going a long distance, or if you are currently in a downpour. Wind may throw things off a bit, but as far as regular straight down rain goes, these are the options. Well, the diagram may shift slight up and down depending on how fast the rain is falling, but the structure is the same. Unless you actually don’t want to run that much because it wastes energy. Then things may change a bit, and you may even have an optimal velocity to run. But that is something for a follow-up post if it ever comes up.

References:

- The Naked Scientists, 2007, “Do you get wetter if you run or walk through rain?” https://www.thenakedscientists.com/articles/questions/do-you-get-wetter-if-you-run-or-walk-through-rain

- Science World, 2011, “Is it drier to walk or run through the rain?” https://www.scienceworld.ca/stories/it-drier-walk-or-run-through-rain/

- Math Pages Blog, 2008, “Running in the rain” https://mathpages.blogspot.com/2008/08/running-in-rain.html

- The Science of Everyday Life, 2009, “Just Walkin’ In The Rain” https://thescienceofeverydaylife.blogspot.com/2009/05/just-walkin-in-rain.html

- MythBusters, (2005), Episode 38, “MythBusters Revisited”

- “Is it worth running?” – http://www.dctech.com/physics/notes/0006.php

- Wikipedia, “Flux”, on March 2024 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flux